Climate Crisis in Operating Theatres: Environmental Effects of Surgery

- Sofiya Star

- Jun 18, 2023

- 6 min read

The effects of the climate crisis are becoming apparent as global temperatures reach unprecedented heights and natural disasters become more frequent (United Nations, 2022). Individuals are now aware of how their actions negatively impact the health of the planet. Using non-sustainable materials, perpetuating carbon emissions by driving in gasoline-fuelled cars and supporting companies that are ecologically harmful are some examples of what people are encouraged to avoid (Fawzy et al., 2020). Humans are the dominant producers of carbon emissions, which have destructive effects on the planet (European Commission, n.d). Yet, human health is also deteriorating due to environmental problems (Rocque et al., 2021). Ironically, the health sector has a prominent carbon footprint (a representation of carbon emissions), being responsible for around 5% of global carbon emissions (Lenzen et al., 2020). This is equivalent to the carbon dioxide released by 514 coal-fired plants in a year (Karliner et al., 2019). More specifically, surgeries have significant input in elevating the energy expenditure and the carbon emissions of the healthcare system. The utilisation of single-use surgical equipment, continued reliance on general anaesthetic and the unsustainable maintenance of operating theatres are key factors that cause surgeries to be ecologically unfriendly practices (Rizan et al., 2020). Hence, this article will explore the current limitations of how surgeries are undertaken in more depth, delving into specific examples, and give alternatives that show promise of making surgical interventions, and therefore the health sector, more environmentally friendly.

How Can Performing Surgeries Damage The Environment?

Single-use equipment

A salient aspect of surgeries is the mitigation of post-operative infections by using sterile, single-use tools that are not shared between patients. Although this process is thought to make surgeries safer, studies have not found decisive evidence that surgeries using reusable equipment pose a greater risk for patients (Das et al., 2020). Yet, the effects of single-use surgical equipment on the environment are clear and detrimental. Operating theatres produce large amounts of waste in the form of single-use surgical equipment, along with the individual wrapping that each product comes in. Research has shown that the packaging of single-use equipment accounts for 80% of the waste produced after surgery (Cunha & Pellino, 2022). The routine is to dispose of the single-use equipment after surgery into a biohazardous waste bin, even if it remained unused; the materials that are placed into these bins end up in landfills or are incinerated, the two most environmentally harmful methods of disposal (Pietrabissa et al., 2022). Additionally, the manufacturing and shipping process of single-use equipment plays a significant role in increasing the carbon footprint of operating theatres. Surgical tools, designed for one-time use, are typically composed of petroleum-based plastic – a non-biodegradable material made out of finite sources (Braschi et al., 2022; Unger et al., 2017). Furthermore, the large-scale production of these products usually occurs overseas. Thus, the shipment of single-use equipment also generates high quantities of greenhouse emissions (gases that are responsible for inducing global warming) before they even reach the hospital (Rodríguez‐Jiménez et al., 2023; Bhutta, 2021). The difficulty persists with equipment that is synthesised from more complex materials, like metal equipment and robotics (Papadopoulou et al., 2022). Catheters are small metal tubes that are used for cardiac surgeries. Rare metals, including platinum and gold, are used for the production of catheter electrodes, which only last for a single surgery. Unlike plastic, for which we have a recycling procedure in motion, the recycling of precious metals is a difficult and lengthy process. Due to this, metals that are not recycled are dumped into landfills, adding to the pollution of the planet (Boussuge-Roze et al., 2022). Hence, the use of disposable equipment in surgeries can have a devastating impact on the health of the planet.

Figure 1: Disposal of solid waste generated in an operating theatre during surgery (Thiel et al., 2015)

Gas Anaesthetics

Before a surgery takes place, the common procedure is to sedate a patient so that they are unconscious during the surgical intervention. This is done through the use of anaesthetics. Gas anaesthetics, including isoflurane, desflurane and nitrous oxide, are widely used pre-operatively because they can rapidly produce a sedating effect when inhaled by a patient (Clar & Richards, 2019). However, gas anaesthetics are powerful greenhouse gases, meaning they can facilitate the trapping of heat energy from the sun to cause global warming. Anaesthetic gases are exhaled by the patient, causing them to accumulate in the atmosphere (Varughese & Ahmed, 2021). Desflurane, a common inhaled anaesthetic, has the strongest contributing effect to the carbon footprint out of all gas anaesthetic; a single gram of desflurane has a global warming impact equivalent to that of 2.45 kilograms of carbon dioxide (Cunha & Pellino, 2022). Therefore, due to the reliance on gas anaesthetics, surgeries are environmentally harmful procedures.

Energy and Water Expenditure

Hospitals are large buildings that are constantly operating, requiring electricity, heating, ventilation and water for them to effectively keep running (Eckelman & Sherman, 2016). Even when not in use, operating theatres are prepped for surgeries and hence, are continuously consuming energy (Rizan et al., 2020). In most cases, before surgery is commenced, imaging tests are done on patients to reach a diagnosis and to guide the surgery (Cunha & Pellino, 2022). Imaging tests, such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and X-rays, use technologies that require large amounts of energy to operate, increasing the consumption of electrical energy even before the patient reaches the operating theatre (Heye et al., 2020). Water is another finite source that is scarce in many areas of the world. However, the need for surgeons to disinfect their hands before putting on sterile gloves and a surgical gown (a process known as surgical scrubbing) can result in large volumes of water being wasted in the operating theatre (Altinoz et al., 2021). A study performed in a hospital in the United Kingdom showed that in a span of a year, surgical scrubbing had contributed to the use of 931,938 litres of water (Jehle et al., 2008). Thus, it can be concluded that a vast amount of energy and natural resources are consumed in preparation for medical surgeries, having a harmful effect on the environment.

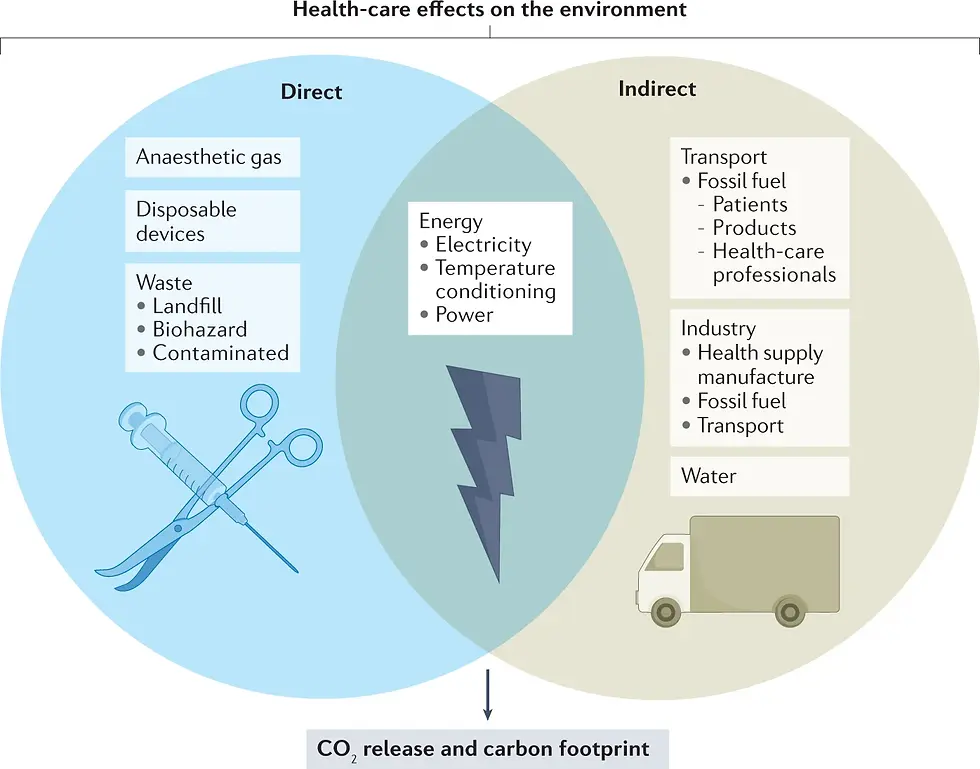

Figure 2: Effects of performing surgery on the environment (Cunha & Pellino, 2022)

How Can Performing Surgeries Become More Sustainable?

The reality of the effects that surgeries have on the environment is disheartening. However, being aware of such problems is important to push for the changes that can make surgeries, and the health sector as a whole, more environmentally friendly (Kah Ann Ho & Naseem, 2023). To mitigate the effect of surgeries on the environment, the 5R principles of waste management (reduce, reuse, recycle, rethink and research) can be used (Hutchins & White, 2009). The reduction of single-use equipment is considered to be the most feasible step that can be taken by the healthcare system to reduce the global carbon footprint (Braschi et al., 2022). Additionally, reducing the use of gas anaesthetics by replacing them with intravenous anaesthetics can be an easily implemented change that would reduce the greenhouse effect. Energy and water consumption can also be addressed by reducing ventilation, heating and electricity use in inactive operating theatres and by using alcohol disinfectants to reduce water waste during surgical scrubbing (Cunha & Pellino, 2022). Reusable surgical equipment should become more widely available and multiple uses of more technologically advanced tools, like endoscopes and catheters, should be encouraged so that they are not discarded prematurely (Keil et al., 2022). Recycling is a simple protocol that can reduce the amount of waste being generated in operating theatres. As some studies suggest that up to 90% of surgical waste can be recycled, educating health professionals about how to correctly recycle in operating theatres can be a significant step towards making surgeries more eco-friendly (Ali et al., 2017). Environmental research in the context of operating theatres can help develop novel ideas on how to deal with current issues. This can include looking into biodegradable materials that can be used to make surgical equipment; finding ways to power hospitals with reusable energy (solar panels, wind power) (Psillaki et al., 2023) and using sensor-taps to lower the volume of water used for surgical scrubbing (Altinoz et al., 2021). Finally, educating health professionals on how medical surgeries are implicated in the climate crisis can help them to rethink how they can play a role in making surgeries more sustainable (Kah Ann Ho & Naseem, 2023).

An inspiring surgery was conducted by a team from the University Hospitals Birmingham National Health Service Foundation Trust (2022) that was termed as ‘carbon neutral’, meaning it produced close to zero carbon emissions throughout the whole clinical process. The team implemented many of the measures discussed above during the surgery, such as using reusable surgical gowns, administering an intravenous anaesthetic, minimising energy use and recycling the packaging and single-use equipment used during the surgery. The surgeons even reduced their individual carbon footprint by cycling and running to the hospital. The team calculated that implementing these changes led to an 80% reduction in carbon release compared to that of a typical surgery. The first documented ‘carbon neutral’ surgery portrays the feasibility of making surgeries more sustainable and gives hope that the health sector can become more environmentally friendly in the future.

Figure 3: A painting of a surgery (Seal, 2016)

Conclusions

The health sector is a prominent contributor to the global carbon footprint, with the most harmful effects on the environment being attributed to surgeries. The energy and water expenditure in the operating theatre, the accumulation of waste and the use of gas anaesthetics are the principal reasons why surgeries have a negative impact on the planet. However, it has been shown that surgeries can be performed with minimal carbon emissions. This can be done through the use of the 5R principles of waste management and by raising awareness among surgeons and health professionals of how their profession is impacting the environment.

Bibliographical References

Ali, M., Wang, W., Chaudhry, N., & Geng, Y. (2017). Hospital waste management in developing countries: A mini review. Waste Management & Research : The Journal of the International Solid Wastes and Public Cleansing Association, ISWA, 35(6), 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X17691344

Altinoz, A., Sheebani, S. A., Mirza, M., Ameri, M. A., Aravind, P., Dembinski, R., & Habibi, M. (2021). Water Consumption during Pre-Operative Hand Sanitisation: A QI Project for the Post-COVID-19 World. Hamdan Medical Journal, 14(2), 78. https://doi.org/10.4103/hmj.hmj_72_20

Bhutta, M. F. (2021). Our over-reliance on single-use equipment in the operating theatre is misguided, irrational and harming our planet. 103(10), 709–712. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsann.2021.0297

Boussuge-Roze, J., Duchateau, J., Bessiere, F., Sacher, F., & Jaïs, P. (2022). Environmental sustainability in cardiology: reducing the carbon footprint of the catheterization laboratory. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 20(2), 69–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-022-00826-2

Braschi, C., Tung, C., & Chen, K. T. (2022). The impact of waste reduction in general surgery operating rooms. The American Journal of Surgery, 224(6), 1370–1373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2022.10.033

Clar, D. T., & Richards, J. R. (2019, October 22). Anesthetic Gases. Nih.gov; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537013/

Cunha, M. F., & Pellino, G. (2022). Environmental effects of surgical procedures and strategies for sustainable surgery. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-022-00716-5

Das, A. K., Okita, T., Enzo, A., & Asai, A. (2020). The Ethics of the Reuse of Disposable Medical Supplies. Asian Bioethics Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41649-020-00114-6

Eckelman, M. J., & Sherman, J. (2016). Environmental Impacts of the U.S. Health Care System and Effects on Public Health. PLOS ONE, 11(6), e0157014. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157014

European Commission. (n.d). Causes of climate change. https://climate.ec.europa.eu/climate-change/causes-climate-change_en#:~:text=CO2%20produced%20by%20human,largest%20contributor%20to%20global%20warming.

Fawzy, S., Osman, A. I., Doran, J., & Rooney, D. W. (2020). Strategies for mitigation of climate change: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 18(18), 2069–2094. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-020-01059-w

Heye, T., Knoerl, R., Wehrle, T., Mangold, D., Cerminara, A., Loser, M., Plumeyer, M., Degen, M., Lüthy, R., Brodbeck, D., & Merkle, E. (2020). The Energy Consumption of Radiology: Energy- and Cost-saving Opportunities for CT and MRI Operation. Radiology, 295(3), 593–605. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020192084

Hutchins, D. C. J., & White, S. M. (2009). Coming round to recycling. BMJ, 338(mar10 2), b609–b609. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b609

Jehle, K., Jarrett, N., & Matthews, S. (2008). Clean and Green: Saving Water in the Operating Theatre. The Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 90(1), 22–24. https://doi.org/10.1308/003588408x242277

Kah Ann Ho, & Naseem, Z. (2023). Greener theatre, greener surgery – environmental sustainability in a rural surgical setup. 93(5), 1134–1140. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.18369

Karliner, J., Slotterback, S., Boyd, R., Ashby , B., & Steele, K. (2019). Health Care's Climate Footprint how the Health Sector Contributes to the Global Climate Crisis and Opportunities for Action [Review of Health Care's Climate Crisis Footprint How the Health Sector contributes to the Global Climate Crisis and Opportunities for Action]. https://noharm-global.org/sites/default/files/documents-files/5961/HealthCaresClimateFootprint_092319.pdf

Keil, M., Viere, T., Helms, K., & Rogowski, W. (2022). The impact of switching from single-use to reusable healthcare products: a transparency checklist and systematic review of life-cycle assessments. European Journal of Public Health, 33(1), 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckac174

Lenzen, M., Malik, A., Li, M., Fry, J., Weisz, H., Pichler, P.-P., Chaves, L. S. M., Capon, A., & Pencheon, D. (2020). The environmental footprint of health care: a global assessment. The Lancet Planetary Health, 4(7), e271–e279. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(20)30121-2

University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust. (2022). Sustainable surgery: the first “net zero” operation in the NHS. https://www.uhb.nhs.uk/news-and-events/news/sustainable-surgery-the-first-net-zero-operation-in-the-nhs/608186

Papadopoulou, A., Kumar, N. S., Vanhoestenberghe, A., & Francis, N. K. (2022). Environmental sustainability in robotic and laparoscopic surgery: systematic review. British Journal of Surgery. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znac191

Pietrabissa, A., Pugliese, L., Filardo, M., Marconi, S., Muzzi, A., & Peri, A. (2022). My OR goes green: Surgery and sustainability. Cirugía Española (English Edition), 100(6), 317–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cireng.2022.06.013

Psillaki, M., Apostolopoulos, N., Makris, I., Liargovas, P., Apostolopoulos, S., Dimitrakopoulos, P., & Sklias, G. (2023). Hospitals’ Energy Efficiency in the Perspective of Saving Resources and Providing Quality Services through Technological Options: A Systematic Literature Review. Energies, 16(2), 755. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16020755

Rizan, C., Steinbach, I., Nicholson, R., Lillywhite, R., Reed, M., & Bhutta, M. F. (2020). The Carbon Footprint of Surgical Operations. Annals of Surgery, 272(6), 986–995. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000003951

Rocque, R. J., Beaudoin, C., Ndjaboue, R., Cameron, L., Poirier-Bergeron, L., Poulin-Rheault, R.-A., Fallon, C., Tricco, A. C., & Witteman, H. O. (2021). Health effects of climate change: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open, 11(6). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046333

Rodríguez‐Jiménez, L., Macarena Romero-Martín, Spruell, T., Steley, Z., & Gómez-Salgado, J. (2023). The carbon footprint of healthcare settings: A systematic review. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jan.15671

Unger, S. R., Hottle, T. A., Hobbs, S. R., Thiel, C. L., Campion, N., Bilec, M. M., & Landis, A. E. (2017). Do single-use medical devices containing biopolymers reduce the environmental impacts of surgical procedures compared with their plastic equivalents? Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 22(4), 218–225. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26746994

United Nations. (2022). What is Climate Change? Climate Action; United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/what-is-climate-change

Varughese, S., & Ahmed, R. (2021). Environmental and Occupational Considerations of Anesthesia: A Narrative Review and Update. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 133(4). https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005504

Visual Sources

Seal, A. (2016, April 15). The Art of Medicine. Thechangingpalette. https://thechangingpalette.com/2016/04/15/the-art-of-medicine/

Cunha, M. F., & Pellino, G. (2022). Environmental effects of surgical procedures and strategies for sustainable surgery. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-022-00716-5

Thiel, C. L., Eckelman, M., Guido, R., Huddleston, M., Landis, A. E., Sherman, J., Shrake, S. O., Copley-Woods, N., & Bilec, M. M. (2015). Environmental Impacts of Surgical Procedures: Life Cycle Assessment of Hysterectomy in the United States. Environmental Science & Technology, 49(3), 1779–1786. https://doi.org/10.1021/es504719g

Comments