Children’s Education in the Era of Extreme Climate Events

- Constance Bwire

- Sep 28, 2025

- 13 min read

Climate change is no longer a distant or future concern; it is already affecting the daily lives of millions across the globe (IPCC, 2023). Among those most at risk are children, whose physical and emotional development makes them especially vulnerable (Ahdoot et al., 2024; UNICEF, 2019). One of the most overlooked dimensions of this crisis is its impact on education (Imray, 2025). As climate-related extreme events, such as heatwaves, floods, wildfires, and storms, become more frequent and intense, schools are facing increasingly serious challenges (Imray, 2025). These disruptions go beyond physical damage to buildings or unsafe roads. They interfere with children’s ability to attend school, concentrate in class, and maintain both their physical health and emotional well-being (Ahdoot et al., 2024; Imray, 2025; IPCC, 2023; Suresh, 2024; Vergunst & Berry, 2022).

Children, defined here as individuals under the age of 18 (UNICEF, n.d.), face heightened risks during environmental crises. Their bodies are more sensitive to heat, making thermoregulation difficult in overheated classrooms (Rowland, 2008; Schapiro et al., 2024). Many also depend on adults for transport and protection, which can render school attendance difficult or impossible during severe weather (Ige-Elegbede et al., 2024; Juel et al., 2023). The global education system, however, remains largely unprepared for these conditions (Imray, 2025; UNICEF, 2019, 2023, 2024). As hazards intensify, the gap widens between children’s needs and what schools can provide.

The consequences for children extend beyond immediate injury. While floods, heatwaves, and storms can cause direct harm, such as injuries, respiratory problems, waterborne diseases, and heat-related illness, they also trigger serious indirect effects (IPCC, 2023; Juel et al., 2023; Pacheco, 2020). When hazards damage crops or undermine livelihoods, food insecurity rises; malnutrition then weakens children’s ability to learn, grow, and resist illness (IPCC, 2023; Lieber et al., 2022; Sheffield & Landrigan, 2011). Crises also interrupt daily routines that support emotional stability (APA, 2023; IPCC, 2023; Venegas et al., 2024). Repeated or prolonged disruptions are associated with anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress, impacts that often go untreated where mental-health services are scarce (APA, 2023).

Schools are central to children’s lives—not only as places of instruction but also as safe environments offering meals, psychosocial support, and structure (Imray, 2025; World Bank, 2024). During emergencies, they can provide shelter, protection, and psychological care. As climate change accelerates and severe weather becomes more frequent, these functions are increasingly at risk. This jeopardizes children’s health and safety and threatens their fundamental right to education, established in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and reaffirmed in numerous treaties. Education systems must therefore adapt rapidly to ensure continuity of learning amid intensifying environmental pressures (IPCC, 2023; Imray, 2025).

Climate disruption in schools: A Global snapshot

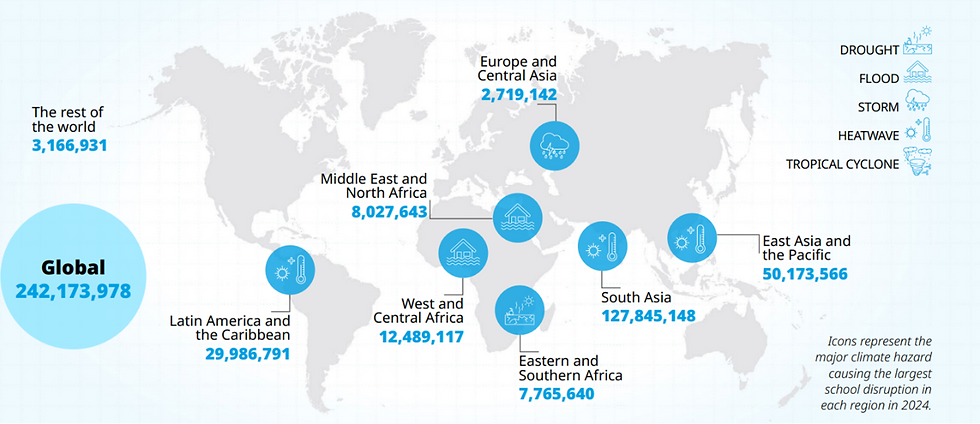

In 2024, climate-related hazards disrupted schooling for at least 242 million children across 85 countries (Imray, 2025; UNICEF, 2025), roughly one in seven school-aged students (UNICEF, 2025). These disruptions are no longer isolated; they’re reshaping schooling worldwide and vary sharply by region (Figure 2).

Heatwaves have emerged as a leading driver of interruption, particularly in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. In April 2024, temperatures exceeded 40 °C across numerous areas, affecting over 118 million children who either missed classes or studied in overheated, poorly ventilated rooms (UNICEF, 2025).

Low- and middle-income countries are disproportionately burdened. Prolonged exposure to severe weather has led to widespread closures, damaged facilities, and interrupted learning for millions, with consequences that extend to mental health and well-being. In Pakistan, the 2022 floods displaced over 33 million people and damaged or destroyed more than 2 million homes. Nearly 27,000 schools were rendered unusable, leaving millions without safe learning environments for extended periods (Nanditha et al., 2023; Samad & Sheikh, 2024). Similar conditions have been documented elsewhere; in the Philippines, some students continued lessons in partially flooded classrooms (Figure 3).

In Mozambique, Cyclone Chido caused extensive damage to the education system. It destroyed over 330 schools and several regional education offices, leaving thousands of children without classrooms (UNICEF, 2024). As illustrated in Figure 3, a flooded classroom exemplifies how extreme weather events continue to disrupt education, particularly in contexts that are already vulnerable.

Similarly, in Afghanistan, a combination of extreme heatwaves and flash floods destroyed more than 110 schools, displacing thousands of students and further straining fragile education services (Imray, 2025; UNICEF, 2025).

Even high-income countries are not exempt. In Italy and Spain, for example, severe flooding displaced hundreds of thousands of students, disrupted academic calendars, and damaged school infrastructure (UNICEF, 2025). In June 2024, a record-breaking heatwave in Greece pushed temperatures to 43°C, prompting nationwide closures of schools and nurseries to ensure student safety (BBC, 2024).

Many schools worldwide remain ill-prepared for climate-related hazards. Most buildings are not designed to withstand severe conditions such as storms, floods, and heatwaves (UNICEF, 2024, 2025; Venegas et al., 2024). Structural weaknesses, fragile walls, and roofs leave classrooms vulnerable (Figure 4). In hot regions, the absence of cooling systems hinders concentration and well-being (Venegas et al., 2024). Basic safety features, clearly marked exits, reinforced foundations, and protective barriers are often missing, heightening risk (UNICEF, 2025). These shortcomings are most acute in low-income areas, where underfunding and poor maintenance are common. Without resilient construction and clear emergency protocols, closures can persist for weeks or months after a disaster (Samad & Sheikh, 2024; UNICEF, 2024, 2025; Venegas et al., 2024).

While temporary closures during hazardous conditions are necessary to protect students from unsafe infrastructure, extended interruptions impede learning and elevate the risk of dropout (Brauchle et al., 2025). Children rely on routine; when disasters or illness disrupt daily school life, confusion, anxiety, and disorientation can follow—especially when usual roles and responsibilities are lost (Brauchle et al., 2025). Crucially, schools are social environments. Beyond academics, they provide spaces for connection and emotional support. Prolonged absences limit opportunities to develop and sustain social skills. As seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, long breaks from in-person learning can foster isolation, impede social development, and compromise emotional well-being (Cameron & Tenenbaum, 2021).

Resilience Is Possible

Across the world, practical strategies are helping education systems become more resilient, safer, and better prepared for future shocks. The following examples show what can be achieved when schools, communities, civil society, and governments act, independently or in partnership.

Strengthening School Infrastructure

Rising temperatures have underscored the need to design facilities that protect student well-being and support uninterrupted learning. A study from a government school in Ambala, India, demonstrates that thermal comfort can be maintained without air conditioning through natural ventilation, shaded areas, and the use of local materials (Jindal, 2018). Similar strategies are employed at the Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls School in Rajasthan, where temperatures often exceed 40 °C; sandstone walls, open courtyards, and a circular layout keep classrooms cool, enabling comfortable learning without fans or air conditioning (Kellogg, 2021).

In Mozambique, over 600 classrooms were strengthened with cyclone-resilient upgrades, including reinforced roofs, elevated concrete foundations, and wind-resistant designs (World Bank, 2024). In Türkiye, 24 schools that adhered to updated seismic codes and integrated earthquake-resistant elements withstood the 2023 earthquakes without structural damage and were used safely as emergency shelters (Galasso & Opabola, 2024; World Bank, 2024).

Indigenous solution for continual learning

Bangladesh offers an innovative model for sustaining education during high water through floating schools (Alam & Zhu, 2023). In low-lying areas like Chalan Beel, where heavy rains prevent students from reaching land-based classrooms, boat schools deliver instruction on board. Built from indigenous materials and powered by solar energy, each vessel accommodates roughly 30–35 students and includes a library, internet connectivity, and potable water. Boats collect students, hold lessons, and return them home safely (Figure 6). In some areas, these schools have yielded pass rates exceeding 99% in national exams.

After floodwaters recede, the boats are often docked and repurposed as mobile libraries, vocational training centers, or community hubs, sustaining educational services while building long-term resilience.

Nature-based solutions

Outdoor spaces designed to mitigate heat—such as schoolyards in Paris’s Oasis Project—show how campuses can remain cooler during heatwaves (Gallez et al., 2024), Figure 7. Replacing expanses of concrete with trees, planting beds, and shade structures improves comfort and safety.

Implementing Early Warning Systems

Integrating real-time alerts into school communications enhances preparedness and supports proactive, safer responses. In Mozambique, SMS-based warnings are sent to schools ahead of cyclones, enabling early evacuation and protection of learning materials (Ferreira, 2019). In India, the School Safety Program uses mobile-app notifications and radio announcements to reach remote schools before floods or heatwaves (Syukron, 2024). The Philippines links meteorological forecasts to school-closure decisions through multi-hazard systems coordinated with local government (Era et al., 2022).

Inclusive Planning

As schools adapt to a changing climate, inclusive planning is essential. Involving students, including those with disabilities, ensures that safety protocols reflect diverse needs. Rather than treating children as passive recipients, participatory approaches recognize their capacity to contribute to risk reduction and resilience. In Portugal, national programs have worked to include students’ voices in emergency planning and school-safety strategies (Delicado et al., 2017). When children with disabilities receive clear, accessible information and participate in regular drills, they develop greater capacity to respond in crises (Jang & Ha, 2021). These efforts show that planning is most effective when students are part of the process; schools become safer, and children feel more confident and included.

Curriculum Integration

Embedding risk and preparedness content in everyday lessons equips students with practical skills to protect themselves and others during extreme weather. Evidence shows that age-appropriate methods, stories, drawings, games, and safety drills build confidence and reduce fear during real events (Ardoin & Bowers, 2020; Krishna et al., 2022; Seddighi et al., 2020). Instruction should also prepare students for post-disaster realities: damaged schools, altered routines, and emotional stress. By learning what to expect and how to cope, adapting to new classrooms, and articulating feelings, students are better positioned to recover and reconnect (Krishna et al., 2022). In this way, curriculum-based resilience supports long-term learning and well-being (Krishna et al., 2022; Seddighi et al., 2020).

Emergency Funding and Insurance

When schools are damaged, rapid financing is essential to resume operations. Dedicated education emergency funds allow governments and districts to repair buildings, install temporary classrooms, replace supplies, and provide transport for displaced students. For example, U.S. federal restart grants have enabled districts to restore facilities, deploy portable classrooms, and offer mental-health and tutoring services after major shocks (GAO, 2022). Likewise, insurance against weather-related damage accelerates recovery by freeing resources for reconstruction and offering reassurance to staff and families. Disaster-risk financing and insurance mechanisms meet post-disaster needs quickly without compromising fiscal stability (GAO, 2022; Panda & Surminski, 2020). In low-income contexts, such instruments can supply faster, more predictable funds to vulnerable communities. With robust funding pools and insurance in place, schools rebound more quickly, minimizing instructional loss (Panda & Surminski, 2020).

Supporting Children’s Minds

Recovery must address both infrastructure and emotional well-being. Major shocks can be traumatic, leaving children confused and distressed; safeguarding psychological health is as crucial as restoring academic continuity. Psychological First Aid (PFA) equips educators to provide immediate emotional care and to triage students needing further support; PFA has been shown to reduce anxiety, re-establish routine, and strengthen resilience (Brymer et al., 2006). Parents also play a critical role. Shared activities, conversation, play, and drawing help children express emotions and feel secure. Because children mirror adult behavior, caregivers should model calm, constructive stress management. Discussing future emergency plans can further enhance preparedness and reduce fear (Broadwater, 2023). Coordinated efforts between schools and families build a support system that promotes recovery, growth, and continued learning.

Final Thoughts

Climate change is already reshaping the way children live and learn; however, this need not determine their future. Around the world, schools, communities, and families are demonstrating that, with the right tools, planning, and support, education systems can adapt and become stronger. From storm-resistant buildings and floating classrooms to mental-health care and inclusive planning, effective solutions exist. What is required now is the will to scale these efforts, especially where needs are greatest. Every child has the right to learn in a safe, supportive environment. By acting now, we can protect that right while ensuring that education survives the climate crisis and helps lead the way forward.

References

Ahdoot, S., Baum, C. R., Cataletto, M. B., Hogan, P., Wu, C. B., Bernstein, A., … Onyema-Melton, N. (2024). Climate change and children’s health: Building a healthy future for every child. Pediatrics, 153(3).https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2023-065505

Alam, M. B., & Zhu, Z. (2023). The floating schools of Bangladesh: An indigenous solution for the lack of access to primary education in flood-prone areas. ECNU Review of Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/20965311231189521

American Psychological Association (APA). (2023). Mental health & our changing climate: Children and youth report. https://www.apa.org/pubs/reports/climate-change-mental-health-children-2023

Ardoin, N. M., & Bowers, A. W. (2020). Early childhood environmental education: A systematic review of the research literature. Educational Research Review, 31, 100353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100353

BBC. (2024). Greek schools close because of “historic” heatwave. BBC Newsround. https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/articles/cd11jenp1r5o

Brauchle, J., Unger, V., & Hochweber, J. (2025). Student wellbeing during COVID-19—Impact of individual characteristics, learning behavior, teaching quality, school system-related aspects and home learning environment. Frontiers in Education, 10, 1518609. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1518609

Broadwater, A. (2023, September 6). Extreme weather events are forcing school closures: Experts explain the mental health toll on kids. Yahoo News. https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/extreme-weather-school-closures-mental-health-kids-204837967.html

Brymer, M., Jacobs, A., Layne, C., Pynoos, R., Ruzek, J., Steinberg, A., Vernberg, E., & Watson, P. (2006). Psychological first aid: Field operations guide (2nd ed.). National Child Traumatic Stress Network; National Center for PTSD. https://www.nctsn.org/resources/psychological-first-aid-pfa-field-operations-guide-2nd-edition

Cameron, L., & Tenenbaum, H. R. (2021). Lessons from developmental science to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 restrictions on social development. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(2), 231–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220984236

Delicado, A., Rowland, J., Fonseca, S., de Almeida, A. N., Schmidt, L., & Ribeiro, A. S. (2017). Children in Disaster Risk Reduction in Portugal: Policies, Education, and (Non) Participation. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 8(3), 246–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-017-0138-5

Era, M., Vallar, E., Osman, A. J., Borg, R. P., Axisa, G. B., Ayerbe, I. A., Gonzalez-Pardo, M. M., & Ranguelov, B. (2022). A Baseline Assessment of the Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems in the Province of Batangas, Philippines. International Journal on Advanced Science, Engineering and Information Technology, 12(2), 621–626. https://doi.org/10.18517/ijaseit.12.2.15003

Ferreira, N, D. (2019). Mobile-Based Early Warning Systems in Mozambique. An exploratory study on the viability to integrate Cell Broadcast into disaster mitigation routines.

Galasso, C., & Opabola, E. A. (2024). The 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquake Sequence: finding a path to a more resilient, sustainable, and equitable society. Communications Engineering, 3(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-024-00170-y

Gallez, E., Fraile Mujica, C. P., Gadeyne, S., Canters, F., & Baró, F. (2024). Nature-based school environments for all children? Comparing exposure to school-related green and blue infrastructure in four European cities. Ecological Indicators, 166, 112374. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOLIND.2024.112374

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). (2022). Disaster Recovery Districts in Socially Vulnerable Communities Faced Heightened Challenges after Recent Natural Disasters Report to Congressional Committees United States Government Accountability Office. (GAO-22-104606). https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-104606.pdf

Ige-Elegbede, J., Powell, J., & Pilkington, P. (2024). A systematic review of the impacts of extreme heat on health and well-being in the United Kingdom. Cities & Health, 8(3), 432–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2023.2283240

Imray, G. (2025, January 24). Nearly 250 million children missed school last year because of extreme weather, UNICEF says. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/climate-weather-children-school-unicef-eb93150ca5c1f79a663f7c6755be3196

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2023). Climate change 2023: Synthesis report (H. Lee & J. Romero, Eds.). https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647

Jang, J. H., & Ha, K. M. (2021). Inclusion of children with disabilities in disaster management. Children, 8(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/children8070581

Jindal, A. (2018). Thermal comfort study in naturally ventilated school classrooms in composite climate of India. Building and Environment, 142, 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BUILDENV.2018.05.051

Juel, R., Sharpe, S., Picetti, R., Milner, J., Bonell, A., Yeung, S., Wilkinson, P., Dangour, A. D., & Hughes, R. C. (2023). Let’s just ask them. Perspectives on urban dwelling and air quality: A cross-sectional survey of 3,222 children, young people and parents. PLOS Global Public Health, 3(4), e0000963. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000963

Kellogg, D. (2021). The Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls School / Diana Kellogg Architects. ArchDaily. Accessed June 21, 2025. Available on https://www.archdaily.com/960824/the-rajkumari-ratnavati-girls-school-diana-kellogg-architects.

Krishna, R. N., Spencer, C., Ronan, K., & Alisic, E. (2022). Child participation in disaster resilience education: potential impact on child mental well-being. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 31(2), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-03-2021-0110

Lieber, M., Chin-Hong, P., Kelly, K., Dandu, M., & Weiser, S. D. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the impact of droughts, flooding, and climate variability on malnutrition. Global Public Health, 17(1), 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1860247

Nanditha, J. S., Kushwaha, A. P., Singh, R., Malik, I., Solanki, H., Chuphal, D. S., Dangar, S., Mahto, S. S., Vegad, U., & Mishra, V. (2023). The Pakistan Flood of August 2022: Causes and Implications. Earth’s Future, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EF003230

Pacheco, S. E. (2020). Catastrophic effects of climate change on children’s health start before birth. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 130(2), 562–564. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI135005

Panda, A., & Surminski, S. (2020). Climate and disaster risk insurance in low-income countries: Indicators and frameworks for monitoring performance and impact. Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics.https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/working-paper-348-Panda-Surminski.pdf

Rowland, T. (2008). Thermoregulation during exercise in the heat in children: old concepts revisited. Journal of Applied Physiology, 105(2), 718–724. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01196.2007

Samad, N., & Sheikh, I. (2024). Catastrophic Sways of Floods on the Education Sector in Pakistan. Academy of Education and Social Sciences Review, 4(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.48112/aessr.v4i1.591

Schapiro, L. H., McShane, M. A., Marwah, H. K., Callaghan, M. E., & Neudecker, M. L. (2024). Impact of extreme heat and heatwaves on children’s health: A scoping review. The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 19, 100335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2024.100335

Seddighi, H., Yousefzadeh, S., López López, M., & Sajjadi, H. (2020). Preparing children for climate-related disasters. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 4(1), e000833. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000833

Sheffield, P. E., & Landrigan, P. J. (2011). Global Climate Change and Children’s Health: Threats and Strategies for Prevention. Environmental Health Perspectives, 119(3), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1002233

Suresh, K. (2024). Extremes of Weather Conditions and Child Health. Open Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health, 9(1), 050–057. https://doi.org/10.17352/ojpch.000058

Syukron, M., Madugalla, A., Shahin, M., & Grundy, J. (2024, July 11). A comprehensive study of disaster support mobile apps [Preprint]. arXiv. https:///doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.08145

UNICEF. (n.d.). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Retrieved June 21, 2025, from https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text-childrens-version.

UNICEF. (2019, December 6). The climate crisis is a child rights crisis: Introducing the Children’s Climate Crisis. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/fact-sheet-climate-crisis-child-rights-crisis.

UNICEF. (2023). Sustainability and Climate Change Action Plan 2023–2030. https://www.unicef.org/documents/sustainability-climate-change-action-plan.

UNICEF. (2024, December 20). Mozambique flash appeal: Tropical Cyclone Chido. https://www.unicef.org/media/166686/file/Mozambique-Flash-20-Dec-2024.pdf. Accessed on 21st June 2025.

UNICEF. (2025). Learning interrupted: Global snapshot of climate-related school disruptions in 2024. https://www.unicef.org/media/170626/file/Global-snapshot-climate-related-school-disruptions-2024.pdf. Accessed on 21st June 2025.

Venegas Marin, S., Schwarz, L., & Sabarwal, S. (2024). Impacts of Extreme Weather Events on Education Outcomes: A Review of Evidence. The World Bank Research Observer, 39(2), 177–226. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkae001

Vergunst, F., & Berry, H. L. (2022). Climate Change and Children’s Mental Health: A Developmental Perspective. Clinical Psychological Science, 10(4), 767–785. https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026211040787

World Bank. (2024, March 8). Building safer and more resilient schools in a changing climate. https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2024/03/08/building-safer-and-more-resilient-schools-in-a-changing-climate.

Visual References

Broadwater, A. (2023). Extreme weather events are forcing school closures. Experts explain the mental health toll on kids still reeling from a natural disaster. Why returning to school after an extreme weather event can bring grief and anxiety. https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/extreme-weather-school-closures-mental-health-kids-204837967.html

UNICEF. (2025). In Learning interrupted: Global snapshot of climate-related school disruptions in 2024. https://www.unicef.org/reports/learning-interrupted-global-snapshot-2024

Magsambol, B. (2022). Tales of school opening: In-person classes, classroom shortage, flooded areas

Ralaivita, A. (2023). Severe weather events increasingly disrupting children’s education in Madagascar. UNICEF Madagascar. https://www.unicef.org/madagascar/en/stories/severe-weather-events-increasingly-disrupting-childrens-education-madagascar

Kellogg, D. (2021). The Rajkumari Ratnavati Girl’s School / Diana Kellogg Architects. https://www.archdaily.com/960824/the-rajkumari-ratnavati-girls-school-diana-kellogg-architects

Alam, Md. B., & Zhu, Z. (2023). The Floating Schools of Bangladesh: An Indigenous Solution for the Lack of Access to Primary Education in Flood-Prone Areas. ECNU Review of Education, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/20965311231189521

Urban Innovative Actions (UIA). (2022). Paris - OASIS. European Union. https://portico.urban-initiative.eu/uia/integrated-development-action/paris-oasis

Comments