Disconnect To Connect

- Mar Estrach

- Dec 9, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Dec 19, 2021

When overstimulation has become a fact of life, I suggest that we reimagine #FOMO as #NOMO, the necessity of missing out, or if that bothers you, #NOSMO, the necessity of sometimes missing out.

– Jenny Odell, from her book “How To Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy”.

JL, J. (2018). [abstract faces of serious people checking their phones except for one, that is happy, looking at a flower] [Illustration]. CNN Philippines. https://cnnphilippines.com/life/culture/2018/07/13/disconnecting-from-social-media.html

Many of us check our phones even before we brush our teeth or start functioning. Somehow, we have acquired the addictive habit—consciously or not—of “just checking” what is going on. Has an emergency popped at work? Has any life-changing event happened overnight? Are my family and friends’ circle doing well?

Technology is already an essential part of us. In almost all spheres of our lives today there is a screen and internet. We spend the day working in front of a screen and then we get off and use another one to escape from the time we spent on the first while at work. The amount of time spent offline is becoming a minor part of our day-to-day activities and this is causing most of us the so-called digital fatigue.

A topic of concern is the fact that we spend more and more time online, which not only affects the eyesight, but also lets us miss out on social interaction away from the screen.

As Scott Wallsten, President and Senior Fellow at the Washington Technology Policy Institute, mentioned in his article What Are We Not Doing When We’re Online: “Each additional minute of time spent online is correlated with 0.27 fewer minutes working; 0.28 fewer minutes spent on other leisure activities, […]; 0.12 fewer minutes sleeping; and 0.05 fewer minutes socializing offline.”

Some of the most relevant areas that suffer from us being online most of the time are:

In-person social interaction: Although we spend a significant amount of time speaking in chats and online conversations, the fact that they are not face-to-face conversations leads to people being less likely to gain social skills, such as knowing how to handle an uncomfortable conversation or learning how to discuss without a screen protecting them. With screens around us there is a tendency to feel a false secure sensation under which people speak or say things they may not say in person, i.e. the hater philosophy in platforms like Twitter. Also, a virtual kiss or hug has not the same healing effect as a physical one, and the social species we are needs an occasional interaction that bristles the skin.

Education: The more we spend time online, the less we spend on education. This measurement is particularly striking when it comes to teenagers and younger people between the ages of 15 and 25, and it is becoming an alarming symptom considering that these are the ages when younger people are forming their characters, interests, and aspirations.

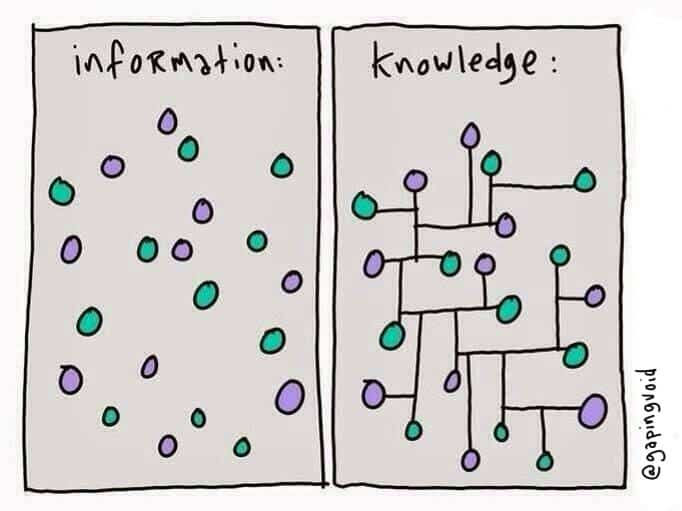

Deep critical thinking: The immense amount of information to which we are exposed these days leads us to frequently multitask while reducing our attention to intermittent and short-term episodes. We jump from one topic to another without dedicating much time to either of them and we do it constantly. This cherry-picking content process allows us to reach plenty of information, which is good to compare sources and points of view, but most of the time it does not catch our attention for more than 2 to 5 minutes before we pass onto the next subject, thus affecting our long-term concentration and analytical thinking. An apparent easy task like sitting and reading a book may seem not so easy if we have gotten into the habit of changing subjects repeatedly. And what about writing an essay for school or a report for work?

Gapingvoid. (2014). [comparison between information and knowledge] [Illustration]. Gapingvoid Culture Design Society. www.gapingvoid.com/blog/2014/01/22/information-vs-knowledge/

Wonder / creativity: In the internet era, the time that people, especially children, dedicate to “doing nothing” has decreased. Most of us have a tendency to grab our smartphones, laptops, or streaming accounts to distract ourselves when we get bored, leaving little room for our brain to wonder; this also happens to the youngest ones. The continuous use of the internet can weaken the memory or creativity, both of which are important for a healthy development. As Teresa Torrecilla, professor from the CEU San Pablo University, mentioned in an interview: “In the past, when children went on a car trip, they would think and put their neurons to work. But today they go all the way with the tablet. This affects the ultimate goal of parents, which is to create a conscious, responsible and free child, and if there is no creativity, there is no freedom”.

Lavado, J. S. (Quino). (n.d.). [Mafalda saying hello to a flower] [Illustration]. Pinterest. Retrieved Dec. 12 2021, from https://ar.pinterest.com/pin/605593481112703121/

Sleep: The internet craving for our constant attention has allowed streaming, gaming, and social media platforms to generate mechanisms that can easily be labelled as addictive (i.e. uploading all the episodes of a season all at once instead of releasing them once a week, the “based on your interests” sections, the automatic algorithm that will jump from one content to another automatically, the “news feed” button, the “unlock levels” challenges, etc), and this has reportedly been proven to affect our sleeping habits. Evenings are our times to “disconnect” and relax, but checking content that triggers addiction is likely to turn the five-minute scroll into one or two hours.

Si, Z. (2021). [two women speaking in bed, one is reading and one is scrolling her phone] [Illustration], The New Yorker Cartoons, https://www.instagram.com/p/CTU9rOnAJB1/

Sense of community: Even though it sounds paradoxical, spending more time online increases the feeling of loneliness among users. Humans need to feel that they belong to a certain group—big or small—and although the internet has made a good job connecting people, something is off when it comes to making individuals feel this sense of belonging. Somehow, seeing other people’s lives online inevitably brings a desire for comparing yourself to them. This is not a problem when a famous person's life is on the screen, but when it comes to someone from a closer network, with similar social status and characteristics, interpretations slightly change. Indeed, this can potentially lead to people feeling bad about what they have or lack in their lives and generate emotions like anxiety, frustration, or competitiveness. On a more extreme level, people may feel less like others due to a stronger sense of isolation, thus increasing a sense of individuality while decreasing a sense of community and empathy for each other, leaving room to a higher risk of manipulation by using a “divide and conquer” culture.

The above is not an exhaustive list of all the areas in which online culture has an impact, but these are some important lines that go to the core of human growth and evolution. Of course, there are many interpretations of reality and it is hard to determine how much of our time spent online is good for us and how much of it is negatively affecting us. There is no dividing line in this regard, but one sure thing is that the extra time we use online comes at the cost of other activities.

Internet connectivity has many benefits, but its main risk lies in the abuses we make of it. We should be able to achieve digital wisdom and do better with our time spent online, while choosing better habits when accessing information.

References:

Odell, J. (2019). How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy.

Wallsten, S. (2013). What Are We Not Doing When We’re Online. National Bureau of Economic Research, p. 2 – 13.

Nisen, M. (2013). These Charts Show What We’re Not Doing Because We’re Online All The Time. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/how-much-time-people-spend-online-2013-10

Azumendi, E. (2016). El uso continuado de internet debilita el pensamiento profundo. El Diario. https://www.eldiario.es/euskadi/euskadi/continuado-internet-debilita-pensamiento-profundo_1_3932054.html

Comments