Language Acquisition in Children

- Federico Piersigilli

- Feb 27, 2023

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 15, 2023

The capacity for linguistics seems to be a natural property of humans: everyone, in natural conditions, can produce a potentially infinite set of original sentences and understand them. How is this capacity developed in human children? Is the linguistic data that we receive in input sufficient to justify our linguistic knowledge?

The Poverty of the Stimulus

Considering linguistic input, a counterargument to the idea that linguistic input is sufficient to explain how children acquire languages was proposed by Noam Chomsky between the 1950s and the 1960s (Chomsky 1957, 1965). Before then, language was generally associated with other kinds of behavior learnable according to a stimulus-response logic, i.e., language consists of a series of behaviors whose learning is determined by the environment. According to this view, the learning mechanism of language is strongly related to the learner’s exposition to feedback mechanisms: adults teach children how to apply the correct grammar and, when children make errors, they correct them. Chomsky argued that this is not the case at all. Language seems to be acquired more than learned, in the sense that the final attainment of language maturity is reached in an uninstructed and instinctual way: no one instructs children on how they should speak; in any case, this kind of instruction is irrelevant to the acquisition process. In a very short time, all children acquire the relevant structure of their native language and use it productively to generate original sentences. Chomsky went even further, claiming that there must be some innate grammar that permits the acquisitional process to happen.

The poverty of the stimulus argument is still the object of controversy, with scholars trying to demonstrate or deny its validity. A research study by Lidz, J., Waxman, S., & Freedman, J. (2003) showed that very young children can recognize complex syntactic structures in a way that cannot be justified by the linguistic input that they have received. On the other side, there is evidence that statistical learning plays a role in the acquisitional processes and, therefore, supports the idea that input has a more prominent role than that attributed to it by Chomsky (Kidd 2012). Leaving aside the relevance of the input, the poverty of the stimulus argument has played a crucial role in the shift from behaviorism to a new approach to linguistics and cognitive sciences.

The Acquisitional Process

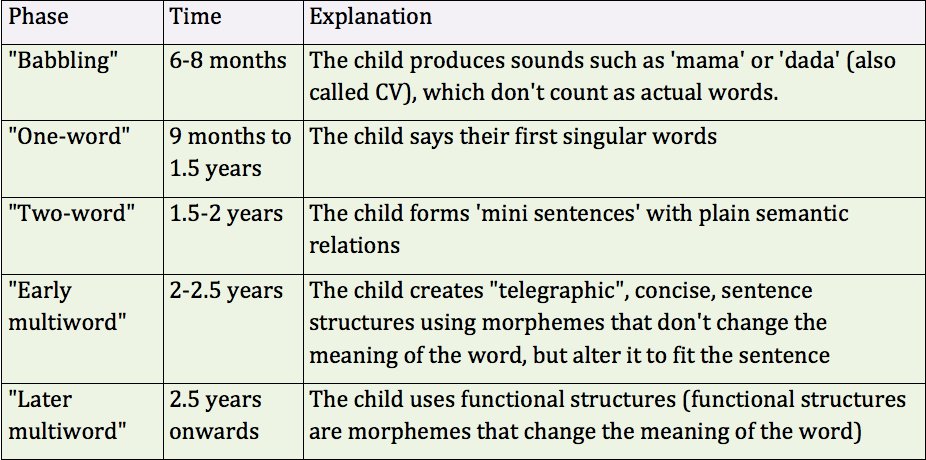

Language acquisition starts at a very early stage in the life of babies (Figure 1). It has been proven that after only 2-3 days, babies can discriminate and recognize acoustic signals and linguistic contrasts, while after 2-3 weeks they are able to distinguish between phonemic units (Mehler & Christophe 2000). In the first months, they show a preference for the way their parents talk over the language of strangers. Furthermore, they can distinguish the difference between different languages (Saffran, Aslin & Newport 1996, Guasti 2007). What kind of clues do babies use to distinguish different languages? Mainly, prosodic features (rhythm and intonation) of a language and phonemic units, i.e., distinctive sounds of that language (par vs. bar). Pre-linguistic vocalizations are present from birth, and they successively evolve according to the development of motor control of muscles involved in sound articulation. Before they are five months old, the sounds produced by babies are very similar in various languages. It is from the last part of the first year that children may manifest the capacity of producing sounds intentionally and with a relational goal, i.e., to transmit them to others. Between the first and the second year, children produce sentences containing 2-3 words. These sentences exhibit the absence of elements like articles, prepositions, and auxiliary verbs. It is between the second and the fifth year that the acquisitional process "explodes" (Figure 3). They show a developed phonological competence and use correctly the main rules in morphosyntax (Cacciari 2011).

Declarative vs. Procedural Knowledge

First, it is necessary to reflect on what kind of cognitive processes are involved in language production and recognition. Language structures have abstract content that is explainable in terms of mental operations (construct a syntactic structure, attribute meaning to words and sentences, etc.), and they also rely on physical mechanisms like vocal articulation and signal perception. So, what kind of knowledge is linguistic knowledge? To answer this question, it may be useful to distinguish two different definitions of “knowing something”: declaratively or procedurally. Declarative knowledge includes all the notions and memories that are learnable intentionally and that are always accessible to consciousness. Learning the content of a book or memorizing a telephone number are instances in which declarative knowledge is used. Although learning a language includes challenges like recognizing lexical forms and storing them in the memory, language does not seem to rely on declarative knowledge. Indeed, it is more similar to tasks that involve procedural knowledge. This kind of knowledge is immediate, instinctive, and executed in an incredibly short time (Figure 4): abilities like driving a car, performing a sports movement, or playing an instrument are cases in which procedural knowledge is involved. As said, language does not seem compatible with declarative processes but appears very similar to procedural ones. After all, producing and understanding utterances in one’s native language is something that takes place without conscious thinking.

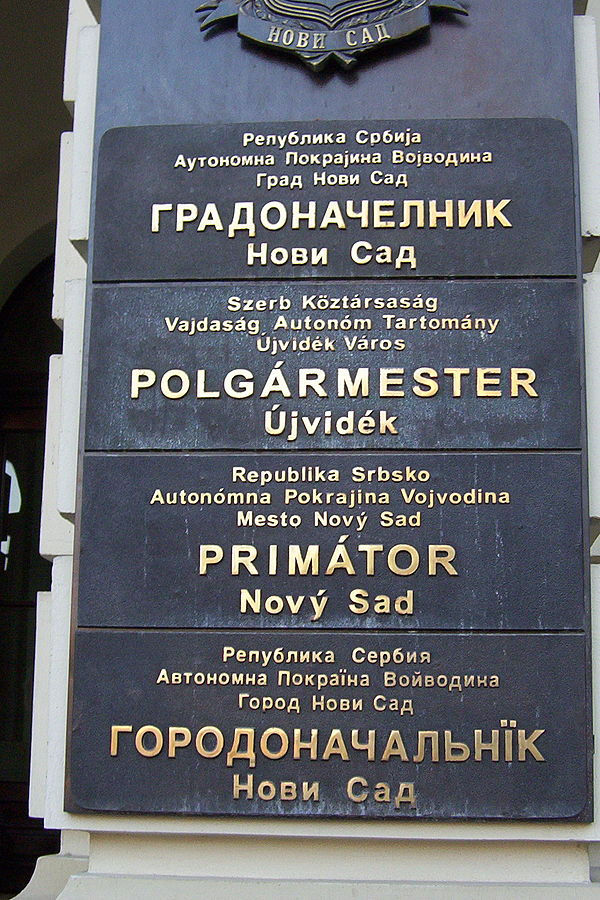

What about the second, third, etc. language? To master a foreign language implies being fluent in that language, i.e., being able to use it naturally and intuitively. But it seems that only a part of bilingual individuals develops this procedural ability with both their native and foreign languages (Figure 2). Why is that? There are several reasons. Many external factors may influence the level of proficiency in other languages, the most relevant ones being the age of acquisition and the quality of input. Especially at the first stages of language learning, declarative knowledge is used to store grammatical structures and use them in language tasks. This is why early learners are not proficient in real-time conversations. They have still not developed a kind of procedural competence in that language.

Conclusion

Language acquisition is a very interesting and complex phenomenon. Children develop the capacity to produce original sentences using correct structures of their language without explicit instruction about the functioning and application of these structures. This fact has led some scholars to hypothesize about the existence of innate structures which drive the acquisitional process. In this case, linguistic input plays a secondary role in the process, being nothing more than a trigger for developing grammar. Others, instead, have claimed that input is the only relevant element in language acquisition and that all structures of the target language are included in this input, by which children extract the relevant information according to mechanisms like statistical learning. While it is not clear yet whether the poverty of the stimulus argument is a valid argument in acquisitional linguistics and to what extent, the unique instinct humans show towards language indicates that there must be some neurobiological basis for such a capacity.

References

Cacciari, C. (2011). Psicologia del linguaggio. Il Mulino.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic structures. The Hague: Mouton.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Guasti, T. (2007). L’acquisizione del linguaggio. Milano, Cortina.

Kidd, E. (2012). Implicit statistical learning is directly associated with the acquisition of syntax. Developmental psychology, 48(1), 171.

Lidz, J., Waxman, S., & Freedman, J. (2003). What infants know about syntax but couldn't have learned: experimental evidence for syntactic structure at 18 months. Cognition, 89(3), 295-303.

Mehler, J. & Christophe, A. (2000). Acquisition of language: Infant and adult data. In M. Gazzaniga (ed.), The new cognitive neurosciences, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Saffran, J. R., Newport, E. L. & Aslin, R. N. (1996). Word segmentation: The role of distributional cues. in Journal of Memory and Language. 35. 606-621

Visual Sources

Cover Image. Emily Nunnell/The Conversation CC-BY-ND, CC BY-SA. https://theconversation.com/curious-kids-how-do-babies-learn-to-talk-111613

Figure 1. Dinglebrob, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2. SlowPhoton, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 3. Parents and children reading a magazine together. The Netherlands, 1958. Nationaal Archief, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 4. G ambrus, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

The first thing I noticed about situs dewapoker was the variety of poker options. From classic Texas Hold’em to other formats, the selection kept me entertained. The platform is stable, and I’ve never experienced interruptions during important games or tournaments.situs dewapoker

Exploring the fascinating realm of language acquisition in children has been a delightful journey with my little ones. I've noticed that interactive toys, available at the kids online shop All4KidsOnline, play a crucial role in enhancing linguistic skills. Their diverse range of educational toys, from interactive storybooks to language-building games, captivates my children's interest for hours. The innovative designs and engaging features make learning a joyous experience. As a parent, I appreciate how All4KidsOnline, a trusted company specializing in children's products, contributes to my kids' cognitive development. These toys not only entertain but also nurture their language abilities, fostering a love for communication from an early age.

Thanks for info!