How ADHD Affects Lives

- Maria McGovern

- Oct 22, 2023

- 8 min read

Updated: Oct 23, 2023

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common neurobehavioral disorders and can affect all aspects of an individual’s life. ADHD usually manifests in young children, though a diagnosis may not come until later. Those who suffer from this disorder are unable to inhibit their spontaneous behaviour, leading to impulsivity and inattention. Inattention is the most common ADHD symptom, presenting in 90 to 95% of adolescents and adults with the condition (Wilens & Spencer, 2010). ADHD can have considerable social and societal consequences for patients if left untreated. Difficulties in personal relationships, underachieving in academic and occupational settings, antisocial behaviour and even reckless driving and delinquency can all be associated with untreated ADHD (Wilens & Spencer, 2010). It was once believed that ADHD symptoms faded after childhood. However, it is now clear that the majority (over 80% of cases) of ADHD patients will still experience symptoms in adulthood and throughout their lives. Clearly, most people will not “grow out” of ADHD (Barkley, 2019).

There is a great deficit in the general public's understanding of ADHD. Those with ADHD are seen as being undisciplined and disruptive. However, the effect of ADHD on a person who suffers from it is far greater than the disruption they may cause to others. Furthermore, as ADHD manifests in childhood, its symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity can be seen as the behaviour of a misbehaving child. As a result, many children are left undiagnosed until adulthood. Children are often ignored or pushed aside in classes and frequently find themselves being disciplined. This leads to further frustration, difficulty learning, behavioural issues and ostracization from society. As with most psychological disorders, the treatment of ADHD is complicated, and the risk of abuse of medications like Ritalin and Adderall is very high (Cramer et al., 2010; Wilens & Spencer, 2010).

ADHD Subtypes and Comorbidities

There are currently three recognised subtypes of ADHD: predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, or a combination. Combined inattentive and hyperactive ADHD is the most common subtype and is usually the most severe and debilitating as the affected individual will experience more symptoms. However, the combined ADHD subtype has shown more stability following treatment than the other subtypes (Wilens & Spencer, 2010).

The social implications of living with ADHD can lead to frustration and the onset of other behavioural issues in affected individuals, particularly young children. Consequently, there can be several other conditions that occur concurrently with ADHD, known as comorbidities. Comorbidities can make many conditions difficult to diagnose due to overlapping symptoms and unclear diagnostic boundaries. There can also be challenges in treating comorbidities, due to pharmacological restrictions, harm to the liver, potential toxicity, and an abundance of side effects. Consequently, it can become complicated to treat a person for multiple conditions at once (Cramer et al., 2010). ADHD can be comorbid with a variety of other psychiatric conditions including oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), as well as mood and anxiety disorders [Figure 2]. In addition, those affected by ADHD have been shown to have an increased likelihood of substance abuse and cigarette smoking (Jensen et al., 1997; Wilens & Spencer, 2010).

ADHD Diagnosis

Like all psychiatric conditions, ADHD can be difficult to diagnose. Diagnosing ADHD involves looking at both symptoms and level of impairment using the guidelines and criteria established in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR), which takes both symptoms and impact on the patient's life into account. There are a total of 18 recognised ADHD symptoms, divided into several categories including inattention (difficulty sustaining attention and mental focus, distractibility and forgetfulness), hyperactivity (fidgeting, restlessness and excessive talking) and impulsivity (difficulty waiting their turn and frequently interrupting others). To obtain an ADHD diagnosis, an individual must exhibit at least six symptoms from two different categories. Furthermore, the condition must have manifested before the age of seven, and be shown to impair at least two areas of life, such as work, school or home life, and have lasted for a minimum period of six months (Wilens & Spencer, 2010).

As the DSM-IV-TR criteria of ADHD symptoms are based on ages up to 17 years old, adult diagnosis of ADHD may not always fit with these criteria. Furthermore, the condition must have onset from at least seven years of age and persist into adulthood. Diagnosing adults with ADHD can therefore be a difficult process, as the existence of the condition in childhood must be established. Considerations of the DSM-IV-TR criteria are taken into account to diagnose adults and establish childhood onset, persistence, and current presence of symptoms. Unlike children, adults have the opportunity to self-diagnose using diagnostic aids such as the Adult Self Report Scale, Conners Adult ADHD Scales, and Brown Attention Scales (Wilens & Spencer, 2010).

ADHD Treatments

There are several different methods that can be employed to treat ADHD. Drugs used to treat this condition belong to the psychostimulant drug class and work by increasing central nervous system (CNS) activity. Medications can be very effective and are widely used in ADHD treatments, but there are a few barriers to their use. For example, the long-term effectiveness of these drugs is still unknown, and they adversely affect sleep, appetite, and growth in many patients. Additionally, many parents and clinicians are reluctant to administer such drugs to children. The most significant drawback to ADHD pharmaceuticals is, however, the potential for prescription drug abuse and misuse (Sonuga‐Barke et al., 2013).

One of the most common pharmaceutical treatments for ADHD is the stimulant drug methylphenidate, which is sold commercially as Ritalin [Figure 4] or Concerta. As a first-line drug treatment (the best initial treatment) with relatively mild side effects, this drug is used to treat many children and adults suffering from ADHD around the world. The mechanism of action of methylphenidate was recently proven by Mizuno and colleagues (2023) by investigating spontaneous neural activity in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) in the CNS following the administration of methylphenidate, and how this affected behavioural changes in volunteer children with ADHD. They showed that this drug works by targeting the NAc to increase dopamine levels in the brain, enhancing cognitive control networks in the patients resulting in more stable and sustained attention spans (Sherzada, 2012).

However, as the rate of prescription for methylphenidate increases, there is also a greater risk of abuse. The recommended starting dose for the methylphenidate drug Ritalin is 5mg, two to three times daily. Increasing the dose as a patient becomes used to the medication increases the risks of abuse (Sherzada, 2012). With higher dosing rates, the potential for accidental overdoses, misuse and use of these drugs in suicide attempts increases. Although the side effects of this drug are usually mild, they increase linearly with dosage. Effects like nervousness, headache, insomnia, anorexia, and tachycardia can become severe, and abuse of this medication resulting in overdose and hospitalisation is associated with more debilitating side effects including hallucinations, psychosis, lethargy, seizures, tachycardia, dysrhythmias, hypertension, and hyperthermia (Klein‐Schwartz, 2002). Furthermore, it has been shown that intranasal abuse of methylphenidate produces similar effects to cocaine. Clinical case studies have demonstrated this, such as Jaffe (1991), who first reported an adolescent patient who took his 200 mg/day prescription of methylphenidate intranasally to produce a "high". This patient developed a dependence on this drug and was admitted to the hospital with symptoms including depression, anxiety, loss of control and being in a suicidal state. Many similar cases have been reported where those prescribed methylphenidate for clinical purposes have abused this drug which resulted in addiction and depression, paranoid and suicidal symptoms (Morton & Stockton, 2000).

One of the most infamous prescription drugs that has often been abused is Adderall [Figure 5]. Adderall is the commercial name for a combination drug made of dextroamphetamine, amphetamine and levoamphetamine. These substances are isomers of amphetamine. Like methylphenidate, Adderall is a psychostimulant, but it has a wider range of targets. Dextroamphetamine works in the CNS to increase dopamine activity in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, while levoamphetamine acts on the peripheral nervous system (PNS) to increase norepinephrine levels. This increased activity is achieved by blocking the reuptake of the dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin neurotransmitters, increasing their availability at neuronal synapses to prolong their signalling effects. The amphetamine component of Adderall also increases dopamine activity by stimulating presynaptic neurons to release more dopamine into the synapse. It also inhibits monoamine oxidase, an enzyme that normally helps to break down neurotransmitters at the synapse. By blocking this enzyme, amphetamine further increases dopamine and norepinephrine action. This combination of methods to increase neurotransmission makes Adderall a powerful and effective tool to treat ADHD (Sherzada, 2012).

Adderall gained notoriety in the 1990s when it became known as the ‘academic steroid.’ Due to its increase in dopamine and norepinephrine activity, Adderall can help focus the mind on the task at hand. For those with ADHD, who struggle with inattention and inability to focus, Adderall can help concentrate long enough to finish tasks, providing a better quality of life. However, for someone who does not have ADHD and therefore no attention deficit, the use of Adderall overstimulates the brain and can produce an intense, overly enhanced focus. This effect has led to Adderall abuse in schools and universities, where students who do not suffer from ADHD have been taking Adderall as a focus enhancer to enable them to study harder and longer. In America, 25% of university students are reported to have used Adderall without a prescription in order to help them study and take exams. As a result, there has been a 400% increase in the sale of Adderall and similar ADHD drugs since the 1990s (Stolz, 2012).

Many patients will choose to explore nonpharmacological interventions to treat ADHD and use pharmacological treatments only in cases where ADHD is severely impacting a patient’s life (Sonuga‐Barke et al., 2013). There are several nonpharmacological treatments for managing ADHD symptoms. Some of these focus on changing the diet, such as excluding artificial food colouring, taking free fatty acid supplements, or restricted elimination diets. There are also psychological treatments such as cognitive training (strengthening neurological processes that are weak in ADHD patients through methods such as using adaptive schedules), neurofeedback (visualising brain activity to show children how to increase attention and develop impulse control), and behavioural interventions (using teaching methods to change ADHD related behaviours) that can be used to improve ADHD symptoms. So far, dietary changes, particularly eliminating artificial colouring, have been shown to offer better improvements for ADHD sufferers than psychological treatments. Psychological treatments may require further study to maximise their effect on ADHD (Sonuga‐Barke et al., 2013).

The effect of these nonpharmacological treatments varies greatly from patient to patient. In many cases, it is recommended that a multimodal approach is the best course of action, where a combination of both pharmacological and nonpharmacological methods are employed for effective ADHD treatment (Cramer et al., 2010).

Conclusion

Although ADHD is one of the most common neurobehavioural disorders, it is not well understood by the public and those who suffer from it are often thought to be simply difficult. A degree of inattention, fidgeting and impulsivity is normal and expected in children, but these behaviours can also be indicators of ADHD. It can be difficult to distinguish these childhood behaviours to obtain an ADHD diagnosis but failure to do so can result in a child being labelled a troublemaker, and lead to further problems at school, work and social encounters for sufferers. Pharmacological treatments like Ritalin and Adderall can help alleviate ADHD symptoms and give a better quality of life but the potential to intentionally or unintentionally abuse these drugs is so great they should only be used in cases where ADHD is debilitating to a patient’s life.

Bibliographical References

Barkley, R. A. (2019). Myth: All children grow out of ADHD. ADHD Awareness Month. https://www.adhdawarenessmonth.org/children‐do‐not‐grow‐out‐of‐adhd. [Accessed on 19 October 2023].

Cramer, A. O. J., Waldorp, L. J., Van Der Maas, H. L. J., & Borsboom, D. (2010). Comorbidity: A network perspective. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x09991567

Jaffe, S. L. (1991). Intranasal abuse of prescribed methylphenidate by an alcohol and drug abusing adolescent with ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(5), 773–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0890-8567(10)80014-0

Jensen, P. S., Martín, D., & Cantwell, D. P. (1997). Comorbidity in ADHD: Implications for research, practice, and DSM-V. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(8), 1065–1079. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199708000-00014

Klein‐Schwartz, W. (2002). Abuse and toxicity of methylphenidate. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 14(2), 219–223. https://doi.org/10.1097/00008480-200204000-00013

Mizuno, Y., Cai, W., Supekar, K., Makita, K., Takiguchi, S., Silk, T. J., Tomoda, A., & Menon, V. (2023). Methylphenidate enhances spontaneous fluctuations in reward and cognitive control networks in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 8(3), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2022.10.001

Morton, W. A., & Stockton, G. G. (2000). Methylphenidate abuse and psychiatric side effects. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 02(05), 159–164. https://doi.org/10.4088/pcc.v02n0502

Sherzada, A. (2012). An analysis of ADHD drugs: Ritalin and Adderall. Johnson Community College Honors Journal, 3(1), 2–15. https://scholarspace.jccc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=honors_journal.

Sonuga‐Barke, E., Brandeis, D., Cortese, S., Daley, D., Ferrín, M., Holtmann, M., Stevenson, J., Danckaerts, M., Van Der Oord, S., Döpfner, M., Dittmann, R. W., Simonoff, E., Zuddas, A., Banaschewski, T., Buitelaar, J. K., Coghill, D., Hollis, C., Konofal, É., Lecendreux, M., & Sergeant, J. A. (2013). Nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of dietary and psychological treatments. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070991

Stolz, S. (2012). CHALK TALKs- Adderall abuse: Regulating the academic steroid. The Journal of Law of Education, 41(3), 585. https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1P3-2710555451/chalk-talks-adderall-abuse-regulating-the-academic. [Accessed on 19 October 2023].

Wilens, T. E., & Spencer, T. (2010). Understanding attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder from childhood to adulthood. Postgraduate Medicine, 122(5), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2010.09.2206.

Visual Sources

Cover Image: Brazier, A. (2023). Why does ADHD still not get the respect it deserves?. [Image]. CADDAC. https://caddac.ca/why-does-adhd-still-not-get-the-respect-it-deserves-by-alison-brazier-ph-d/

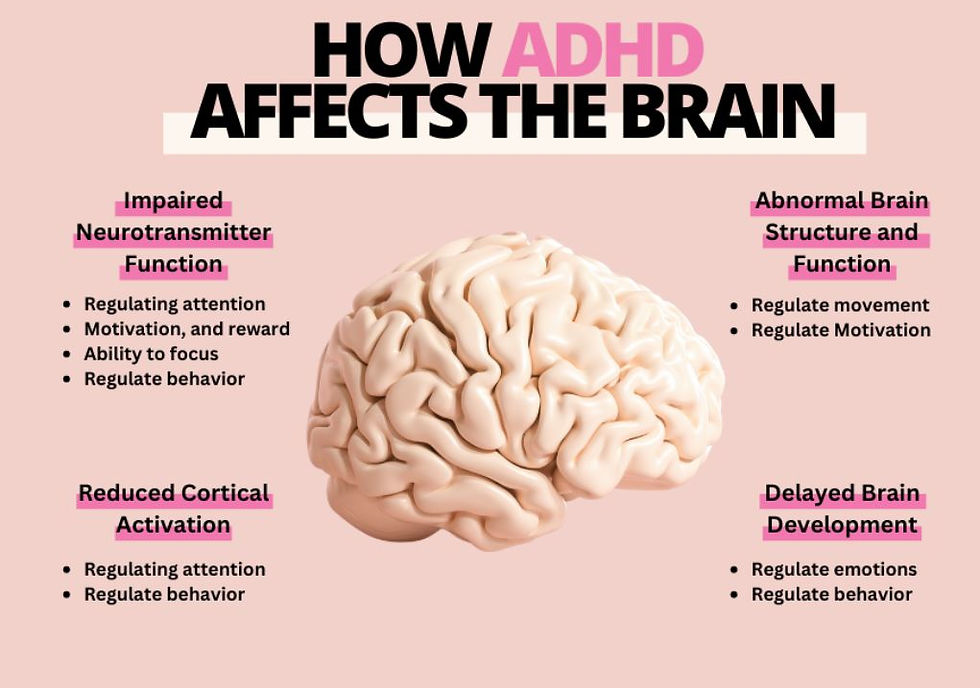

Figure 1: Özgümüş, B. (2023). [How ADHD affects the brain]. [Image]. Insumo. https://www.insumo.io/post/understanding-the-7-types-of-adhd-using-habit-tracking-to-manage-adhd

Figure 2: Hutten, M. (n.d.). ADHD comorbidities. [Image]. My Aspergers Child. https://www.myaspergerschild.com/2018/09/test.html

Figure 3: Neff, D. (2023). [Examples of ADHD diagnosis criteria]. [Image]. Neurodivergent Insights. https://neurodivergentinsights.com/blog/dsm-5-criteria-for-adhd-explained-in-pictures

Figure 4: George, J. (2021). Ritalin medication. [Image]. Medpage Today. https://www.medpagetoday.com/neurology/alzheimersdisease/94722

Figure 5: Constantino, A.K. (2023). Adderall medication. [Image]. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2023/08/26/adhd-drug-market-back-to-school-supply-strain.html

Truy cập uu88me.com – link chính thức và an toàn của nhà cái UU88, đảm bảo không bị chặn, tốc độ mượt mà và hỗ trợ đầy đủ tính năng đăng ký, nạp rút, tham gia cá cược nhanh chóng.

Địa chỉ: 12 Thoại Ngọc Hầu, Phú Trung, Tân Phú, Hồ Chí Minh 72006, Việt Nam

Phone: 0961999812

Gmail: uu88me@gmail.com

Website: https://uu88me.com/

Hastag: #uu88, #uu88me, Nhà_cái_uu88, #uu88mecom, uu88_com, Thương_hiệu_uu88, uu88_link

Simple but effective graphics, fun sounds create excitement when playing." Although not too fussy about the image, basket random still brings a pretty good visual and audio experience.